- 482 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

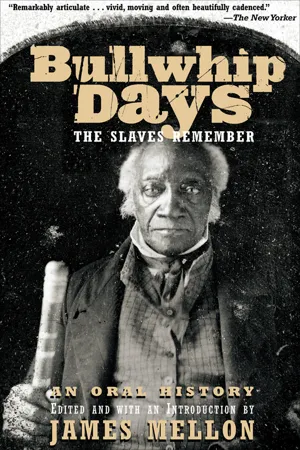

"Twenty-nine oral histories and additional excerpts, selected from 2000 interviews with former slaves conducted in the 1930s for a WPA Federal Writers Project, document the conditions of slavery that . . . lie at the root of today's racism." —

Publishers Weekly

In the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration commissioned an oral history of the remaining former slaves. Bullwhip Days is a remarkable compendium of selections from these extraordinary interviews, providing an unflinching portrait of the world of government-sanctioned slavery of Africans in America. Here are twenty-nine full narrations, as well as nine sections of excerpts related to particular aspects of slave life, from religion to plantation life to the Reconstruction era. Skillfully edited, these chronicles bear eloquent witness to the trials of slaves in America, reveal the wide range of conditions of human bondage, and provide sobering insight into the roots of racism in today's society.

"Remarkably articulate . . . vivid, moving, and beautifully cadenced." — The New Yorker

In the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration commissioned an oral history of the remaining former slaves. Bullwhip Days is a remarkable compendium of selections from these extraordinary interviews, providing an unflinching portrait of the world of government-sanctioned slavery of Africans in America. Here are twenty-nine full narrations, as well as nine sections of excerpts related to particular aspects of slave life, from religion to plantation life to the Reconstruction era. Skillfully edited, these chronicles bear eloquent witness to the trials of slaves in America, reveal the wide range of conditions of human bondage, and provide sobering insight into the roots of racism in today's society.

"Remarkably articulate . . . vivid, moving, and beautifully cadenced." — The New Yorker

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bullwhip Days by James Mellon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Narratives

NEAL UPSON

CHARLIE DAVENPORT

ELLEN BETTS

NEAL UPSON

GOOD mornin’, Miss. How is you? Won't you come in? I would ax you to have a cheer [chair] on the porch, but I has to stay in de house ‘cause de light hurts my eyes.

Miss, I’s mighty glad you come today, ‘cause I does git so lonesome here by myself. My old ‘oman wuks up to de court'ouse, cookin’ for de folkses in jail, and it's allus late when she gits home. ‘Scuse me for puttin’ my old hat back on, but dese old eyes jus’ can't stand de light even in de hall, ‘less I shades ‘em.

Lawsy, Missy, does you mean dat you is willin’ to set and listen to old Neal talk? ‘Tain't many folkses what wants to hear us old niggers talk no more. I jus’ loves to think back on dem days, ‘cause dem was happy times—so much better'n times now. Folkses was better den. Dey was allus ready to help one another, but jus’ look how dey is now!

I was borned on Marster Frank Upson's place down in Oglethorpe County, nigh Lexin'ton, Georgy. Marster had a plantation, but us never lived dar, for us stayed at de home place what never had more'n ‘bout eighty acres of land round it. Us never had to be trottin’ to de sto’ evvy time us started to cook, ‘cause what warn't raised on de home place, Marster had ‘em raise out on de big plantation. Evvthing us needed t'eat and wear was growed on Marse Frank's land.

Harold and Jane Upson was my daddy and mammy; only folkses jus’ called Daddy “Hal.” Both of ‘em was raised right dar on de Upson place whar dey played together whilst dey was chillun. Mammy said she had washed and sewed for Daddy ever since she was big enough, and when dey got grown dey jus’ up and got married. I was deir only boy and I was de baby chile, but dey had four gals older'n me. Dey was: Cordelia, Anne, Perthene, and Ella. Ella was named for Marse Franks onliest chile, little Mis’ Ellen, and our little mis’ was sho’ a good little chile.

Daddy made de shoes for all de slaves on de plantation and Mammy was called de house ‘oman. She done de cookin’ up at de big ‘ouse and made de cloth for her own fambly's clothes, and she was so smart us allus had plenty t'eat and wear. I was little and stayed wid Mammy up at de big ‘ouse and jus’ played all over it, and all de folkses up dar petted me.

Aunt Tama was a old slave too old to wuk. She was all de time cookin’ gingerbread and hidin’ it in a little trunk what sot by de fireplace in her room. When us chillun was good, Aunt Tama give us gingerbread, but if us didn't mind what she said, us didn't git none. Aunt Tama had de rheumatiz and walked wid a stick, and I could git in dat trunk jus’ ‘bout anytime I wanted to. I sho’ did git ‘bout evvything dem other chillun had, swappin’ Aunt Tama's gingerbread. When our white folkses went off, Aunt Tama toted de keys, and she evermore did make dem niggers stand round. Marse Frank jus’ laughed when dey made complaints ‘bout her.

In summertime dey cooked peas and other veg'tables for us chillun in a washpot out in de yard in de shade, and us et out of de pot wid our wooden spoons. Dey jes’ give us wooden bowls full of bread and milk for supper.

Marse Frank said he wanted ‘em to learn me how to wait on de white folkses’ table up at de big ‘ouse, and dey started me off wid de job of fannin’ de flies away. Mist'ess Serena, Marse Frank's wife, made me a white coat to wear in de dinin’ room. Missy, dat little old white coat made me git de onliest whuppin’ Marse Frank ever did give me. Us had comp'ny for dinner dat day and I felt so big showin’ off ‘fore ‘em in dat white coat dat I jus’ couldn't make dat turkey wing fan do right. Dem turkey wings was fastened on long handles, and atter Marster had done warned me a time or two to mind what I was ‘bout, the old turkey wing went down in de gravy bowl, and when I jerked it out it splattered all over de preacher's best Sunday suit. Marse Frank get up and tuk me right out to de kitchen, and when he got through brushin’ me off I never did have no more trouble wid dem turkey wings.

Evvybody cooked on open fireplaces, dem days. Dey had swingin’ racks what dey called cranes to hang de pots on for b'ilin’. Dere was ovens fer bakin’, and de heavy iron skillets had long handles. One of dem old skillets was so big dat Mammy could cook thirty biscuits in it at one time. I allus did love biscuits, and I would go out in de yard and trade Aunt Tama's gingerbread to de other chilluns for deir sheer of biscuits. Den dey would be skeered to eat de gingerbread, ‘cause I told ‘em I'd tell on ‘em. Aunt Tama thought dey was sick and told Marse Frank de chilluns warn't eatin’ nothin’. He axed ‘em what was de matter and dey told him dey had done traded all deir bread to me. Marse Frank den axed me if I warn't gittin’ enough t'eat, ‘cause he ‘lowed dere was enough dar for all. Den Aunt Tama had to go and tell on me. She said I was wuss den a hog atter biscuits, so our good marster ordered her to see dat li'l Neal had enough t'eat.

PLATE 32: Slaves cooked for their owners at kitchen fireplaces like this one.

I ain't never gwine to forgit dat whuppin’ my own daddy give me. He had jus’ sharpened up a fine new ax for hisself, and I traded it off to a white boy named Roar what lived nigh us when I seed him out tryin’ to cut wood wid a sorry old dull ax. I sold him my daddy's fine new ax for five biscuits. When my daddy found out ‘bout dat, he ‘lowed he was gwine to give me somepin’ to make me think ‘fore I done any more tradin’ of his things. Mist'ess, let me tell you, dat beetin’ he give me evermore was a-layin’ on of de rod.

I used to cry and holler evvy time Mis’ Serena went off and left me. Whenever I seed ‘em gittin’ out de carriage to hitch it up, I started beggin’ to go. Sometimes she laughed and said, ‘All right, Neal.” But when she said, “No, Neal,” I snuck out and hid under de high-up carriage seat and went along jus’ de same. Mist'ess allus found me ‘fore us got back home, but she jus’ laughed and said, “Well, Neal's my little nigger, anyhow.”

Dem old cord beds was a sight to look at, but dey slept good. Us cyarded [carded] lint cotton into bats for mattresses and put ‘em in a tick what us tacked so it wouldn't git lumpy. Us never seed no iron springs, dem days. Dem cords, crisscrossed from one side of de bed to de other, was our springs, and us had keys to tighten ‘em wid. If us didn't tighten ‘em ewy few days, dem beds was apt to fall down wid us. De cheers was homemade, too, and de easiest-settin’ ones had bottoms made out of rye splits. Dem oak-split cheers was all right, and sometimes us used cane to bottom de cheers, but evvybody lakked to set in dem cheers what had bottoms wove out of rye splits.

Marster had one of dem old cotton gins what didn't have no engine. It was wukked by mules. Dem old mules was hitched to a long pole what dey pulled round and round, to make de gin do its wuk. Dey had some gins in dem days what had treadmills for de mules to walk in. Dem old treadmills looked sorter lak stairs. But most of dem gins was turned by long poles what de mules pulled. You had to feed de cotton by hand to dem old gins, and you sho’ had to be keerful or you was gwine to lose a hand and maybe a arm. You had to jump in dem old cotton presses and tread de cotton down by hand. It tuk most all day long to gin two bales of cotton, and if dere was three bales to be ginned, us had to wuk most all night to finish up.

Dey mixed wool wid de lint cotton to spin thread to make cloth for our winter clothes. Mammy wove a lot of dat cloth and de clothes made out of it sho’ would keep out de cold. Most of our stockin's and socks was knit at home, but now and den somebody would git hold of a sto'-bought pair for Sunday-go-to-meetin’ wear.

Colored folkses went to church wid deir own white folkses and set in de gallery. One Sunday, us was all settin’ in dat church listenin’ to de white preacher, Mr. Mansford, tellin’ how de old Debil was gwine to git dem what didn't do right.

Missy, I jus’ got to tell you ‘bout dat day in de meetin'ouse. A nigger had done run off from his marster and was hidin’ out from one place to another. At night he would go steal his somepin'-t'-eat. He had done stole some chickens and had ‘em wid him up in de church steeple whar he was hidin’ dat day. When daytime come, he went off to sleep lak niggers will do when dey ain't got to hustle, and when he woke up, Preacher Mansford was tellin’ ‘em ‘bout how de Debil was gwine to git de sinners.

Right den a old rooster, what he had stole, up and crowed so loud it seemed lak Gabriel's trumpet on Judgment Day. Dat runaway nigger was skeered, ‘cause he knowed dey was gwine to find him sho’, but he warn't skeered nuffin’ compared to dem niggers settin’ in de gallery. Dey jus’ knowed dat was de voice of de Debil what had done come atter ‘em. Dem niggers never stopped prayin’ and testifyin’ to de Lord, till de white folkses had done got dat runaway slave and de rooster out of de steeple. His marster was dar and tuk him home and give him a good, sound thrashin’.

Slaves was ‘lowed to have prayer meetin’ on Tuesday and Friday round at de diffunt plantations whar deir marsters didn't keer, and dere warn't many what objected. De good marsters all give deir slaves prayer meetin’ passes on dem nights so de patterollers wouldn't git ‘em and beat ‘em up for bein’ off deir marsters lands. Dey most nigh kilt some slaves what dey cotch out, when dey didn't have no pass.

White preachers done de talkin’ at de meetin'ouses, but at dem Tuesday and Friday night prayer meetin's, it was all done by niggers. I was too little to ‘member much ‘bout dem meetin's, but my older sisters used to talk lots ‘bout ‘em, long atter de War had brung our freedom. Dere warn't many slaves what could read, so dey jus’ talked ‘bout what dey had done heared de white preachers say on Sunday. One of de fav'rite texties was de third chapter of John, and most of ‘em jus’ ‘membered a line or two from dat.

Missy, from what folkses said ‘bout dem meetin's, dere sho’ was a lot of good prayin’ and testifying ‘cause so many sinners repented and was saved. Sometimes at dem Sunday meetin's at de white folkses’ church, dey would have two or three preachers de same day. De fust one would give de text and preach for at least a hour, den another one would give a text and do his preachin’, and ‘bout dat time another one would rise up and say dat dem fust two brudders had done preached enough to save three thousand souls, but dat he was gwine to try to double dat number. Den he would do his preachin’, and atter dat one of dem others would git up and say, “Brudders and sisters, us is all here for de same and only purpose—dat of savin’ souls. Dese other good brudders is done preached, talked, and prayed, and let the gap down. Now I'm gwine to raise it. Us is gwine to git ‘ligion enough to take us straight through dem pearly gates. Now, let us sing whilst us gives de new brudders and sisters de right hand of fellowship.” One of dem old songs went sort of lak dis:

Must I be born to dieAnd lay dis body down?

When dey had done finished all de verses and choruses of dat dey started:

Amazin’ grace, how sweet de soundDat saved a wretch lak me.

’Fore dey stopped dey usually got round to singin’:

On Jordan's stormy banks I stand,And cast a wishful eye,To Canaan's fair and happy land,Whar my possessions lie.

Dey could keep dat up for hours, and it was sho’ good singin’, for dat's one thing niggers was born to do—to sing when dey gits ‘ligion.

When old Aunt Flora come up and wanted to jine de church, she told ‘bout how she had done seed de hebbenly light and changed her way of livin’. Folkses testified den ‘bout de goodness of de Lord and His many blessins what He give to saints and sinners, but dey is done stopped givin’ him much thanks anymore. Dem days, dey ‘zamined folkses ‘fore dey let ‘em jine up wid de church. When dey started ‘zaminin’ Aunt Flora, de preacher axed her, “Is you done been borned again, and does you believe dat Jesus Christ done died to save sinners?” Aunt Flora, she started to cry, and she said, “Lordy, is He daid? Us didn't know dat. If my old man had done scribed for de paper lak I told him to, us would have knowed when Jesus died.” Missy, ain't dat jus’ lak one of dem old-time niggers? Dey jus’ tuk dat for ign'ance and let her come on into de church.

Dem days, it was de custom for marsters to hire out what slaves dey had dat warn't needed to wuk on deir own land, so our marster hired out two of my sisters. Sis’ Anna was hired to a fambly ‘bout sixteen miles from our place. She didn't lak it dar, so she run away and I found her hid out in our tater ‘ouse. One day when us was playin’, she called to me right low and soft lak and told me she was hongry and for me to git her somepin'-t'-eat, but not to tell nobody she was dar. She said she had been dar widout nothin’ t'eat for several days. She was skeered Marster might whup her. She looked so thin and bad I thought she was gwine to die, so I told Mammy. Her and Marster went and brung Anna to de ‘ouse and fed her. Dat pore chile was starved most to death.

Marster kept her at home for three weeks and fed her up good. Den he carried her back and told dem folkses what had hired her dat dey had better treat Anna good and see dat she had plenty t'eat. Marster was drivin’ a fast hoss dat day, but bless your heart, Anna beat him back home. She cried and tuk on so, beggin’ him not to take her back dar no more, dat he told her she could stay home. My other sister stayed on whar she was hired out till de War was over and dey give us our freedom.

Daddy had done hid all Old Marster's hosses when de Yankees got to our plantation. Two of de ridin’ hosses was in de smokehouse and another good trotter was in de hen'ouse. Old Jake was a slave what warn't right bright. He slep’ in de kitchen and he knowed whar Daddy had hid dem hosses, but dat was all he knowed. Marster had give Daddy his money to hide, too, and he tuk some of de plasterin’ off de wall in Marster's room and put de box of money inside de wall. Den he fixed dat plasterin’ back so nice you couldn't tell it had ever been tore off.

De night dem Yankees come, Daddy had gone out to de wuk ‘ouse to git some pegs to fix somepin'—us didn't have no nails, dem days—when de Yankees rid up to de kitchen door and found Old Jake by hisself. Dat pore old fool was skeered so bad he jus’ started right off babblin’ ‘bout two hosses in de smoke'ouse and one in de hen'ouse, but he was tremblin’, so he couldn't talk plain. Old Marster heared de fuss dey made and he come down to de kitchen to see what was de matter. De Yankees den ordered Marster to git dem his hosses. Marster called Daddy and told him to git dem his hosses, but Daddy, he played foolish lak and stalled round lak he didn't have good sense. Dem sojers raved and fussed all night long ‘bout dem hosses, but dey never thought about lookin’ in de smoke'ouse and hen'ouse for ‘em, and ‘bout daybreak dey left widout takin’ nothin’. Marster said he was sho’ proud of my Daddy for savin’ dem good hosses for him.

Marster had a long pocketbook what fastened at one end wid a ring. One day, when he went to git out some money, he dropped a roll of bills dat he never seed, but Daddy picked it up and handed it back to him right away. Now, my Daddy could have kept dat money jus’ as easy, but he was a ‘ceptional man and believed ewybody ought to do right.

One time Marster missed some of his money and he didn't want to ‘cuse nobody, so he ‘cided he would find out who had done de debbilment. He put a big rooster in a coop wid his haid stickin’ out. Den he called all de niggers up to de yard and told ‘em somebody had been stealin’ his money, and dat evvybody must git in line and march round dat coop and tetch it. He said dat when de guilty ones fetched it, de old rooster would crow. Evvybody fetched it ‘cept one old man and his wife; dey jus’ wouldn't come nigh dat coop whar dat rooster was a-lookin’ at evvybody out of his little red eyes. Marster had dat old man and ‘oma...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- Narratives

- Voices: Slave Children, Food and Cooking, Stealing, and Fading Remembrances of Africa

- Narratives

- Voices: Ghosts and Conjuring

- Narratives

- Voices: Plantation Life, Poor White Folks, Classes of Slaves, Patrollers, Christmas on the Plantation, Dancing, Corn-shuckings, Hog-killings, Music, Slave Marriages, and Forced Breeding

- Narratives

- Voices: Religion and Education

- Narratives

- Voices: Bullwhip Days

- Narratives

- Voices: Slave Auctions, Forced Breeding, Rape, and Runaways

- Narratives

- Voices: The Civil War and Statutory Freedom

- Narratives

- Voices: The Reconstruction Era, Sharecropping, Voting, and the Ku Klux Klan

- Narratives

- Voices: The Younger Generation, Reflections and Conclusions